Traditional Japanese farmhouses (kominka) are masterpieces of regional adaptation, reflecting the climate, natural resources, and cultural practices of their respective areas. While these structures share common elements, their designs, materials, and layouts exhibit remarkable diversity shaped by the environment and societal needs. This article explores the regional distinctions of kominka, their significance, and the challenges associated with their preservation and relocation.

Unique Regional Designs of Kominka

Structural Adaptations to Climate

The design of kominka varies significantly based on regional weather patterns:

- Snowy Regions: In areas with heavy snowfall, such as Niigata or Akita, roofs are designed to withstand significant loads. This requires robust, thick wooden columns to support the weight.

- Warm Coastal Areas: In milder coastal regions, lighter structural designs suffice, reflecting the reduced burden of snow and the need for better ventilation.

Locally Sourced Materials

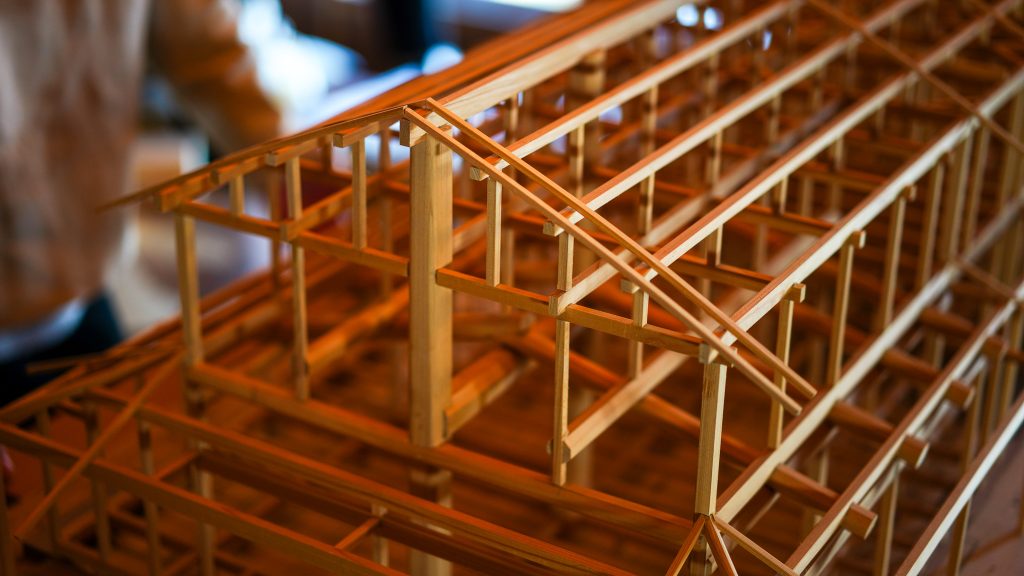

Kominka were traditionally constructed using wood harvested locally, making the type of timber a marker of regional identity:

- Akita: Akita cedar, prized for its strength and beauty.

- Niigata, Gifu, and Shiga: Keyaki (zelkova), known for its durability and rich grain.

- Kyoto Townhouses: North Kyoto cedar logs and peeled round pillars.

- Western Hyogo: Chestnut wood, valued for its resistance to rot.

This regional specificity of materials reflects the integration of natural resources into the architecture, creating homes uniquely suited to their environment.

Distinctive Layouts by Region

The layout of kominka is also tailored to regional lifestyles and needs:

- Kansai Region: The “yotsumadori” design features four rooms arranged in a square (tanoji shape).

- Shinshu (Nagano): Larger layouts such as 3×2 or 3×3 grids are common.

- Tohoku: The magariya, an L-shaped layout, integrates stabling for livestock—a practical solution for snowy areas.

Each layout showcases a deep understanding of local conditions, addressing factors like climate and social organization.

Architectural Features Reflecting Local Challenges

Climate-Driven Innovations

Kominka evolved to handle specific environmental challenges:

- Okinawa: Homes feature low eaves and tall stone walls to withstand typhoons.

- Urban Townhouses: Fire-resistant plaster (shikkui) walls and raised ornamental roofs (udatsu) helped prevent the spread of fires.

- Snowy Regions: High-set windows ensured light during heavy snowfall, while communal arcade-style walkways protected pedestrians.

These features demonstrate the ingenuity of traditional builders in harmonizing design with environmental demands.

Preservation and Relocation of Kominka

The Rise of Relocation Practices

As kominka faced abandonment in the early 2000s, efforts to relocate these structures gained momentum. The process involves moving a house to a new location to save it from demolition. However, relocating a kominka from regions like Niigata to Kansai often results in a visual and cultural mismatch with the surrounding architecture.

- Integration Challenges: Even when the building itself is exceptional, its integration into a new community can disrupt the aesthetic harmony of the area.

- Cultural Sensitivity: Relocation must consider local architectural styles and use materials that blend with the destination’s environment.

Relocation as a Last Resort

Relocation is viewed as a final option for preservation:

- Primary Approach: Rehabilitate and reuse the structure in its original location, maintaining its context and regional significance.

- Secondary Option: If local restoration is unfeasible due to financial, environmental, or logistical constraints, explore relocation as an alternative to demolition.

This approach ensures that relocation is only undertaken when absolutely necessary, prioritizing preservation in the original context wherever possible.

Steps for Kominka Preservation

- Rehabilitation at the Original Site:

Efforts should first focus on revitalizing the kominka at its original location. This retains its cultural and historical integrity while preserving the unique connection between the building and its environment. - Relocation for Preservation:

If rehabilitation is not viable, relocation offers a way to save the structure. The relocation process must respect the architectural style of the new area and strive to integrate the kominka seamlessly into its new surroundings.

Looking Ahead: Balancing Tradition and Modern Needs

Kominka stand as testaments to the adaptability and craftsmanship of traditional Japanese architecture. Their designs reflect the wisdom of past generations in creating homes perfectly suited to their environments. While preservation efforts face challenges, a thoughtful and strategic approach can ensure these structures remain valuable cultural assets for future generations.

Preserving kominka is not just about saving buildings—it’s about honoring a legacy of regional identity, craftsmanship, and environmental harmony that continues to inspire today.

Hitoshi Sato(Architect / CEO of Mokuzo-architect COCHI)

Mokuzou-architect COCHI do not buy the timber for their construction-projects from timber-markets, instead going to the mountains to buy directly from their trusted mountain foresters. With the slogan "To leave the world a beautiful landscape for 300 years to come", the company builds beautiful and resilient houses using the best materials, techniques, and designs. To build awareness of the origins of these trees, grown and tended by many generations of Yamamori, Kochi has started a tour that connects the mountains with the people who live in these special wooden houses.